A tale of betrayal, as told by a Bengali newspaper published from Assam, left me dumb-founded. From March 22, officers from the election commission went door to door in As-sam to help octogenarians (and septuagenarians who were Covid-19 survivors) to vote via paper ballot from their own house. A humanitarian endeavour on the part of the Commission, one may think. In my native state, West Bengal, too, such measures were taken. But the news that I am talking about comprises a terrible complaint. An old wom-an in Assam complained that the personnel from the election commission forced her to vote for the symbol of ‘lotus’, grabbing the opportunity to misuse his power in the ab-sence of her family members. Apart form being a horrific example of state oppression, the incident is a metaphor for a larger truth. A woman’s vote, no matter what her age, has seldom proven to be ‘her own vote’. From the family to the State, it is controlled by various people, mostly men, at various levels.

As a presiding officer, I went to conduct voting in a remote village of the South 24 Par-ganas in West Bengal. Elderly women came leaning on sons and grandsons. The men wished to accompany them to the voting compartment and even cast vote for them. ‘They hardly know whom to vote’, they said, infantalising the elderly women on the ba-sis of their physical frailty and the supposed mental and intellectual ineptness of women in general. The women themselves, too, seemed confused. “Don’t men know better than us?”, their facial expression said.

Women who were not infirm or aged, who came to vote on their feet, too, hardly seemed to have any ‘agency’. A woman surrenders to the ‘gotra’ of his husband in the process of the Hindu marriage. At the same time, over the course of the election, she sur-renders to the political creed and symbol of her in-laws. Often during campaigning, one may hear the patriarch of a family committing to the campaigner of a particular party that all the votes from his family will go to that party. How one can commit on behalf of all the members, one wonders.

When my booth was almost empty in the afternoon, the alertness of one of the three polling agents hinted that someone special might have come. A girl, clad in salwar-suit and her head covered with orhni, entered the room. The agent introduced her as his wife. She was well acquainted with the EVM, but not with the new unit called VVPAT. The agent instructed his wife from the outside, “Make sure you see the symbol in the VVPAT slip.” She got more confused and failed to keep a watchful eye on the VVPAT screen. He then rebuked her publicly and said,’You are good for nothing.’

The body language of the likes of him often betrays them and clearly states how ‘you-are-good-for-nothing’ is the essence of what they think of the female polling officials as well. The female polling officers need to be doubly cautious, as a result. A female presid-ing officer knows that any of her mistakes will be deemed as evidence of the incapability of her gender.

As the election approached, misogyny and gender-discrimination was exhibited for eve-ryone to see across the country, even in West Bengal. Female candidates were not spared. Fake porn pictures were circulated in the case of Rafika Sultana from Murshidabad As-sembly Constituency. She is a non-party, independent candidate. After it was reported in the thana, the miscreants were arrested, but she continued to receive online threats.

A study shows that in over 29 countries 44% of female politicians have received threats of murder, rape or abduction, or faced those crimes in reality. As it was reported, in West Bengal, Meenakshi Mukherjee, a female candidate, was stopped while entering her own constituency and also received veiled threats. On the other hand, Mukherjee’s party con-tinued with their narrative of unapologetic denial of Tapasi Malik’s rape and murder even in 2021. The brutal incident took place fourteen years back, when Mukherjee’s party was there in power.

As we continue to encounter the unceasing misogynist rhetoric spewed by male politicians, we could not help doubting their commitment to the women-centric agendas of their own manifestos. In West Bengal, even small-screen stars, Debaleena And Sayoni, were slandered with gang-rape threats for simply airing their voice on freedom of choice, freedom of choosing what to eat and cook. Later, one of the victims was promptly declared as a candidate from another party. Parliamentary politics utilised the woman’s victimhood, as often as it does.

Mamata Banerjee, the chief minister of West Bengal, is no less maligned for being a woman. The Prime Minister himself hisses out banteringly, ‘Didi, Oooo Didi!’ in a public meeting, a tune that became an ‘instant hit’ with street-harassers, as per reports.

The state secretary of BJP in West Bengal, Dilip Ghosh, advised the chief minister to wear bermudas because she was seen keeping her injured leg lifted up in her public meetings, revealing a part of her leg, which according to Ghosh was ‘unbecoming of a Bengali woman’. When he was asked about the aforesaid comment on a TV channel, he waved off the woman questioner with an entitled, masculine jibe, ‘Nyakami korben na’ (Don’t show me your silly, affected attitudes).

Hoardings, memes and slogans, too, were replete with misogyny. As one party adopted the slogan ‘Bengal wants her own daughter’, the opposition tauntingly implied a daughter, being paraya dhan, should be soon driven out of her paternal home. People even compared the sexual appeal of various women contestants and termed some of them as ‘kajer mashi’ (maids) in memes.

The most intimidating and shocking incident however was reported from Tarakeswar. It was reported that a CAPF jawan attempted to sexually abuse a minor girl who had gone to bring books from a friend’s house. Local people rescued her and reported the incident to Tarakeswar thana and the matter was recorded. The Chairperson of West Bengal Child Protection and Child Rights Commission rushed to the spot on April 7 and met the vic-tim and her family who were seemingly traumatised. She also wrote to the Election Commission requesting that the jawans not be allowed to move from Tarakeswar as they were to be charged under POCSO, 2012, for the gruesome offence. But on April 8 in a press meet she said that the jawans were allowed to leave Tarakeswar and reach their next posting.

The CAPF commanding officer also lodged a counter complaint against the girl and her family on April 7 claiming the previous complaint to be false. Objectionable things were said casually about the girl’s character.

The jawans are deployed to keep the law and order so as to ensuring safe polling. It is unfortunate if they themselves are reported to violate the law and harm even a minor. It is also unfortunate that the POCSO is being violated grossly, endangering the security of minors who are the most vulnerable.

In a society that is patriarchal as a whole, the role of a woman in an election is either that of a puppet or that of a victim and Kolkata is no exception. As a presiding officer and a gender rights activist, I could hardly ignore the fact that transgender people did not come to my booth and neighbouring booths. Neither did the sector officer ask for the account of trans voters, while they readily collected all data related to male and female voters.

In Assam, women have been the worst victims of NRC. An anxious Saira Bibi jumped into the well, though her name finally appeared in the list. Reziya Khatun travelled 250 kilometres to attend a NRC hearing and breathed her last in the queue. Shefali Hajong, a construction labourer, was found carrying bricks on the site of a would-be detention camp that was going to be her own abode thereafter.

The election system is one that gives us the liberty to choose between limited and not-so-ideal options, has its own lacunae and those limitations become more prominent when seen from the perspective of the women and the trans community. However as long as patriarchy persists, the season of elections comes and goes, otherising us every time.

(This article first appeared on Feminism in India)

Liberation Archive

- 2001-2010

- 2011-2020

-

2021-2030

-

2021

- Liberation, JANUARY 2021

- Liberation, FEBRUARY 2021

- Liberation, MARCH 2021

- Liberation, April 2021

-

Liberation, May 2021

- CPI(ML) Foundation Day Call and Resolve

- Modi Shrugs Off Responsibility As India Gasps For Breath

- Fighting CoVID-19, Fighting a Pandemic of Cruel and Irresponsible Misinformation

- Rohingyas: Genocide in the Backyard

- Assembly Elections: BJP’s Communalism, Repression, EVM Fraud, Misogyny At Its Height

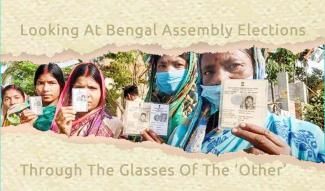

- Looking At Bengal Assembly Elections Through The Glasses Of The ‘Other’

- CM Yogi orders Digging of Well to Douse Already Raging Fire

- Campaign to Save Historic Khudabakhsh Library in Patna

- Poisonous Liquor Deaths in Bihar: Prohibition Fails

- Bhagalpur: Brutal Police Killing of Government Employee

- Nitish Kumar has Shamed Democracy

- No Relief for SHG Women in Bihar Budget

- Recruitment and Justice Convening Committee formed in Patna

- Continuing Massacre of Democracy in Myanmar

- Release Thin Thin Aung

- Al Nakba Anniversary: Saluting the Revolutionary Resistance of Palestinian People

- Condemn the police killing of 5 coal plant workers in Bangladesh

- US Navy Violates India’s Maritime Sovereignty

- Resist Duterte’s Witch-Hunt in Philippines

- Obituary

- Liberation, JUNE 2021

- Liberation, JULY 2021

- Liberation, AUGUST 2021

-

2021

Charu Bhawan, U-90, Shakarpur, Delhi 110092

Phone: +91-11-42785864 | Fax:+91-11-42785864 | +91 9717274961

E-mail: info@cpiml.org